Disclaimer: Opinions expressed are solely my own and do not reflect the views or opinions of my employer or any other affiliated entities. Any sponsored content featured on this blog is independent and does not imply endorsement by, nor relationship with, my employer or affiliated organisations.

Hey everyone. Been quiet on here for a bit. First post of 2026.

I came across a paper that finally articulates something I've been thinking about for a while: autonomy isn't a capability score. It's a design decision"Levels of Autonomy for AI Agents". And chasing the highest level everywhere is a mistake.

Let me walk through it.

L1 (Operator): User directs and makes decisions, agent acts. Think Microsoft Copilot. The agent requires invocation to act, provides on-demand assistance, and avoids preference-based decision-making on the user's behalf.

L2 (Collaborator): User and agent collaboratively plan, delegate, and execute. Think OpenAI Operator. Users can freely modify agent work and take control at any point. Back-and-forth communication is frequent.

L3 (Consultant): Agent takes the lead but consults user for expertise and preferences. Think Gemini Deep Research. Users provide feedback and directional guidance rather than hands-on collaboration. The agent bears more of the learning curve.

L4 (Approver): Agent engages user only in risky or pre-specified scenarios. Think Devin. Users specify approval conditions upfront. The agent only stops for blockers, credentials, or consequential actions.

L5 (Observer): Agent operates with full autonomy under user monitoring. Users can watch activity logs and hit the emergency stop. That's it.

The key insight: autonomy is a design decision, not a capability metric. A capable agent can still operate at L2 if that's the right call for the task. The paper explicitly argues against treating autonomy as an inevitable consequence of increasing capability.

Agency vs. Autonomy

The paper makes an important distinction that matters for security operations.

Agency is the capacity to carry out intentional actions. It's about what tools the agent has access to and what it can do in the environment.

Autonomy is the extent to which the agent operates without user involvement. It's about when and how the agent checks in with humans.

An agent with high agency (many tools, broad permissions) can still have low autonomy (checks in frequently). An agent with low agency (limited toolset) can have high autonomy (runs independently within that scope).

This distinction matters because security teams often conflate the two. Giving an agent access to more data sources (agency) is different from letting it act without approval (autonomy). You can expand agency while constraining autonomy.

Mapping Autonomy to Security Operations

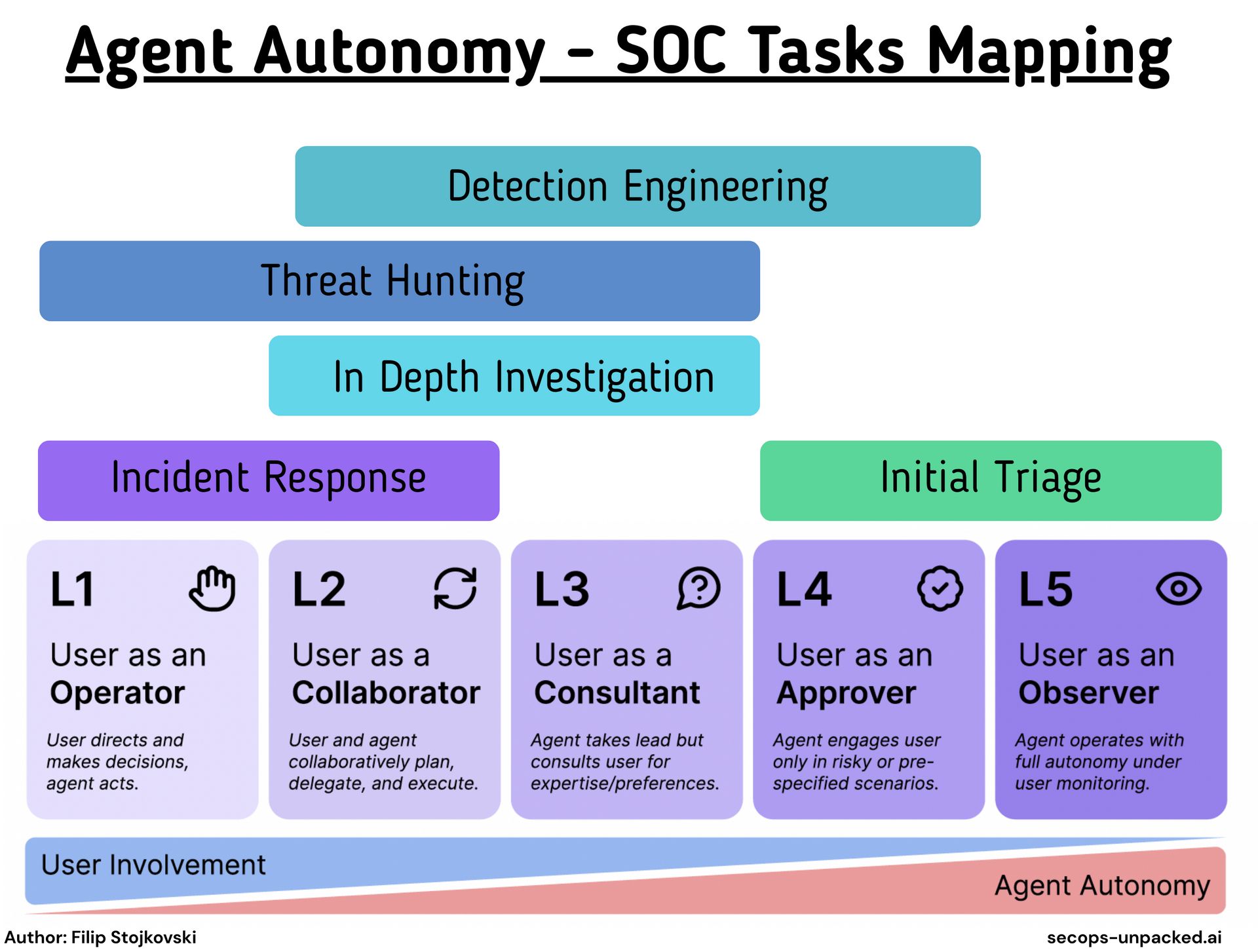

I mapped common security workflows to appropriate autonomy levels based on their risk profile and decision complexity.

Initial Triage: L4-L5

For alert triage, scale beats precision. You're dealing with volume. The goal is filtering, not final judgment.

L4 makes sense here. Let agents do the heavy lifting, have them seek approval only for edge cases or high-severity alerts. L5 is reasonable for low-fidelity alerts where false positives cost nothing. Start at L4. Keep humans reviewing outcomes for anything that escalates to investigation.

The paper notes that L4 agents are ideal for tasks with high amounts of lower-stakes decision-making. Alert triage fits this description. Automated decisions improve efficiency. Erroneous decisions on individual alerts don't impose catastrophic risks if the escalation path is intact.

Incident Response: L1-L2

On the response side of the IR cycle, L1 and L2 work well. These are established patterns with runbooks and playbooks.

Why keep autonomy low here? Response actions are consequential. Isolating a host, blocking a domain, killing a process. These actions have real impact. Speed matters, but accountability matters more.

L1 is appropriate when analysts drive the workflow and agents execute specific tasks on command. L2 works when you want the agent to propose containment plans while the analyst retains takeover capability.

The paper describes L2 control mechanisms as requiring "control transfer from agent to user, and vice versa" plus "shared representation of progress." That maps well to incident response dashboards where analysts can see what the agent is doing and intervene.

In-Depth Investigation: L3

Deep investigation is judgment-heavy work. Context matters. The analyst brings domain knowledge, institutional memory, and threat intelligence the agent doesn't have.

L3 fits this workflow. The agent leads the investigation, gathering data, correlating events, building timelines. But it consults the analyst for direction. What's the hypothesis? Which threads are worth pulling? Does this pattern match something we've seen before?

The paper notes that L3 agents require "productive and timely consultation." The agent needs to know what expertise the user brings and when to ask for it. For security investigations, this means the agent should surface findings and ask about relevance rather than drawing conclusions autonomously.

Threat Hunting: L2-L3

Hunting is exploratory by nature. You're looking for things you don't know exist yet. Hypotheses matter. Intuition matters.

Collaboration beats full automation here. L2-L3 is the range. The agent surfaces anomalies, suggests investigation paths, runs queries. The human drives the hunt itself.

The paper describes L2 as the level where "back-and-forth communication between the user and the agent is the most frequent and rich." Threat hunting benefits from this dynamic. The hunter's domain expertise combined with the agent's ability to process large datasets creates a feedback loop that pure automation can't replicate.

Detection Engineering: L2-L3

Detection engineering is systematic but consequential. Bad detections create alert fatigue. Missed detections create gaps.

L2 is the baseline. The agent assists with query building, suggests detection patterns, helps test against historical data. The engineer retains control over what gets deployed.

L3 is appropriate for mature teams with well-governed detection lifecycles. The agent drafts detections, runs validation, and consults the engineer before deployment. The key is having proper testing and review controls already in place.

The paper warns about L4 agents and "meaningless rubber stamping" from user disengagement. This risk is real for detection engineering. If engineers just approve whatever the agent proposes, detection quality will degrade.

The Double-Edged Sword

The paper repeatedly emphasizes that autonomy amplifies both benefits and risks. Higher autonomy means more scale and efficiency. It also means errors compound over multiple steps without intervention.

This maps directly to security operations. An agent that autonomously closes false positive alerts at L5 saves analyst time. An agent that autonomously closes true positive alerts at L5 creates security incidents.

The paper also raises concerns about deskilling and loss of critical thinking when automation takes over judgment tasks. Security teams should consider this. If agents handle all investigation, what happens to analyst skill development? L2 and L3 autonomy levels preserve opportunities for human engagement while still providing automation benefits.

Autonomy Certificates

The paper proposes "autonomy certificates" as a governance mechanism. A third-party body evaluates an agent's behavior and certifies the maximum autonomy level at which it can operate.

This concept has implications for security vendors. Right now, every AI SOC vendor claims some version of autonomous operation. There's no standard way to compare what that actually means.

An autonomy certificate framework would force clarity. Does your agent operate at L3 or L4? What approval mechanisms exist? Under what conditions does it escalate?

For security buyers, this creates better evaluation criteria than vague claims about AI capabilities.

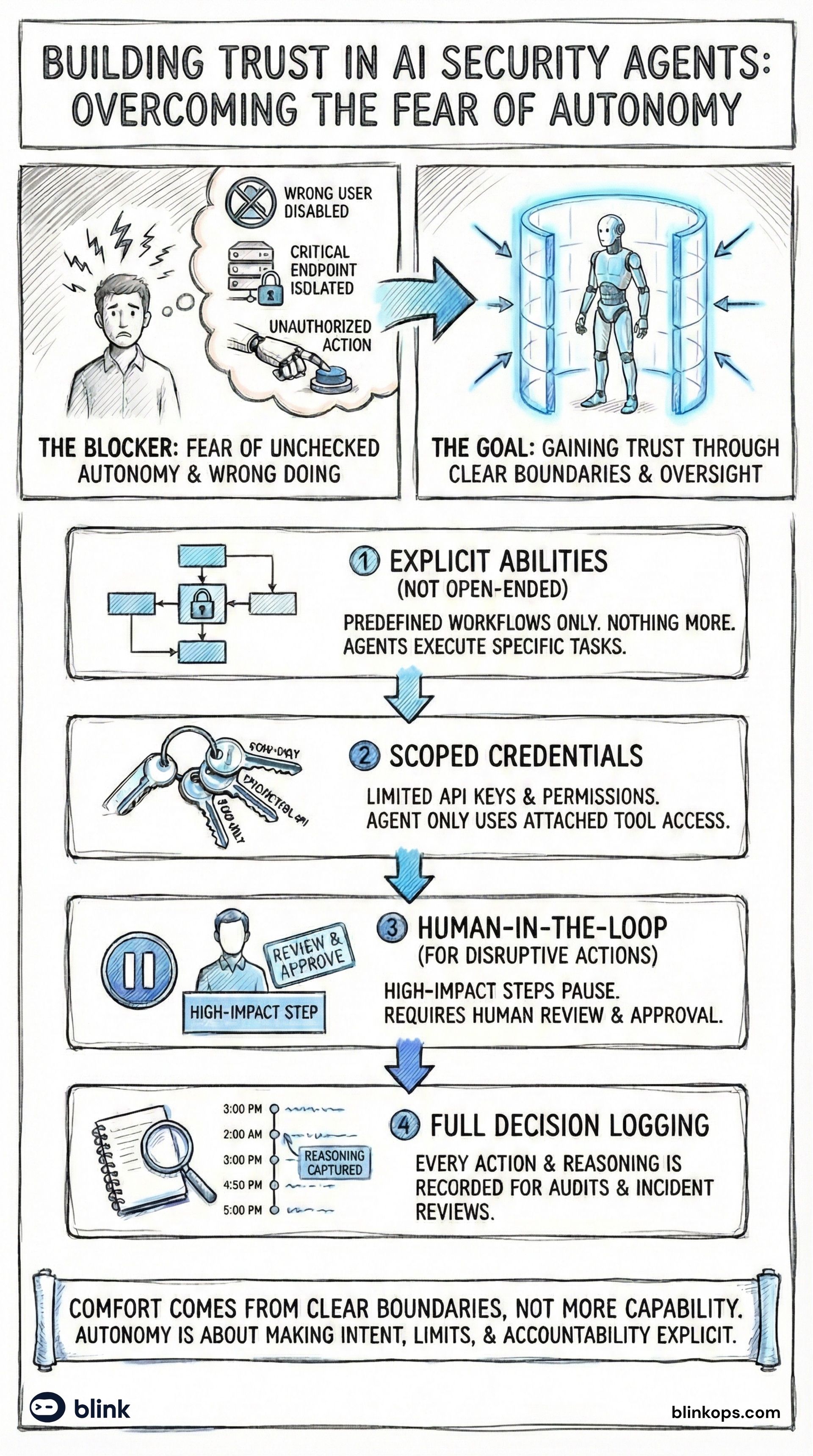

Double-Layer Governance: Reasoning and Abilities

The agency vs. autonomy distinction from the paper points to a practical governance model. You need to control both what the agent can think about doing and what it can actually do.

At BlinkOps, we implement this as double-layer governance:

Layer 1: Reasoning Constraints

This layer limits what the agent can decide to do. It's autonomy governance. You define the scope of problems the agent is allowed to reason about and the types of conclusions it can reach.

For example, an agent handling alert triage might be constrained to reason only about severity classification and enrichment. It can't decide to initiate response actions, even if it has the technical capability. The reasoning boundary is set before the agent ever considers what actions to take.

This maps to the paper's definition of autonomy as "the extent to which an AI agent is designed to operate without user involvement." By constraining reasoning scope, you limit how far the agent goes before involving a human.

Layer 2: Ability Constraints

This layer limits what the agent can execute. It's agency governance. Even if the agent reasons its way to a valid conclusion, it can only act through explicitly permitted capabilities.

This is your tool allowlist. The agent might determine that isolating a host is the right response, but if host isolation isn't in its permitted action set, it can't execute. It has to escalate.

This maps to the paper's definition of agency as "the capacity to carry out intentional actions." By constraining the toolset, you bound the blast radius of any autonomous decision.

Why Both Layers Matter

Single-layer governance creates gaps.

If you only constrain abilities (Layer 2), the agent can still reason about actions outside its scope and make recommendations that push humans toward decisions the agent shouldn't influence. An agent without response permissions might still conclude "this host should be isolated immediately" and create pressure for hasty action.

If you only constrain reasoning (Layer 1), the agent might find edge cases where its reasoning scope overlaps with dangerous capabilities. A triage agent reasoning about "enrichment" might decide that querying a production database for context falls within scope.

Double-layer governance closes both gaps. The reasoning layer defines intent boundaries. The ability layer enforces execution boundaries. An action only happens if it passes both checks.

Practical Implementation

For each workflow, define:

Reasoning scope: What questions can the agent answer? What conclusions can it reach? What types of decisions are out of bounds?

Action permissions: What tools and integrations can the agent invoke? What parameters can it set? What requires human approval?

Escalation triggers: When reasoning hits scope boundaries, where does it go? When actions require approval, who approves?

This gives you granular control without blocking automation entirely. An L4 agent can still operate autonomously within its defined scope. But that scope is explicitly bounded at both the reasoning and execution layers.

The paper's framework helps here. L4 requires "customizable conditions for seeking approval." Double-layer governance operationalizes this. The conditions are defined by reasoning scope violations (Layer 1) and action permission requirements (Layer 2).

What This Means for AI SOC Design

If you're building or buying AI-powered security tooling, ask different questions:

What autonomy level does this workflow need? Not "how autonomous is this agent?" Match the autonomy to the task risk profile.

What are the must-have controls? Each autonomy level has required control mechanisms. L4 requires approval elicitation for consequential actions and customizable conditions. L2 requires control transfer mechanisms and shared progress visibility. Verify these exist.

Where are the approval gates? Every workflow should have defined checkpoints. Know what triggers human involvement.

What's the fallback? When the agent hits a failure state, what happens? The paper notes that L4 and L5 agents should iterate on solutions or modify approaches when blocked. How does your agent handle this?

Who's accountable? Higher autonomy means harder accountability tracing. The paper cites research showing it's simultaneously more important and more difficult to anticipate harms from autonomous AI. Design governance around this reality.

Closing Thoughts

Chasing L5 everywhere is a design mistake, not a strategy.

The vendors pushing "fully autonomous SOC" are selling a destination most teams shouldn't want to reach. The right autonomy level varies by task, by maturity, by risk tolerance.

The paper's framework gives us a shared vocabulary for these discussions. Use it.

Reference: Feng, K.J.K., McDonald, D.W., & Zhang, A.X. (2025). Levels of Autonomy for AI Agents. University of Washington. arXiv:2506.12469

Join as a top supporter of our blog to get special access to the latest content and help keep our community going.

As an added benefit, each Ultimate Supporter will receive a link to the editable versions of the visuals used in our blog posts. This exclusive access allows you to customize and utilize these resources for your own projects and presentations.